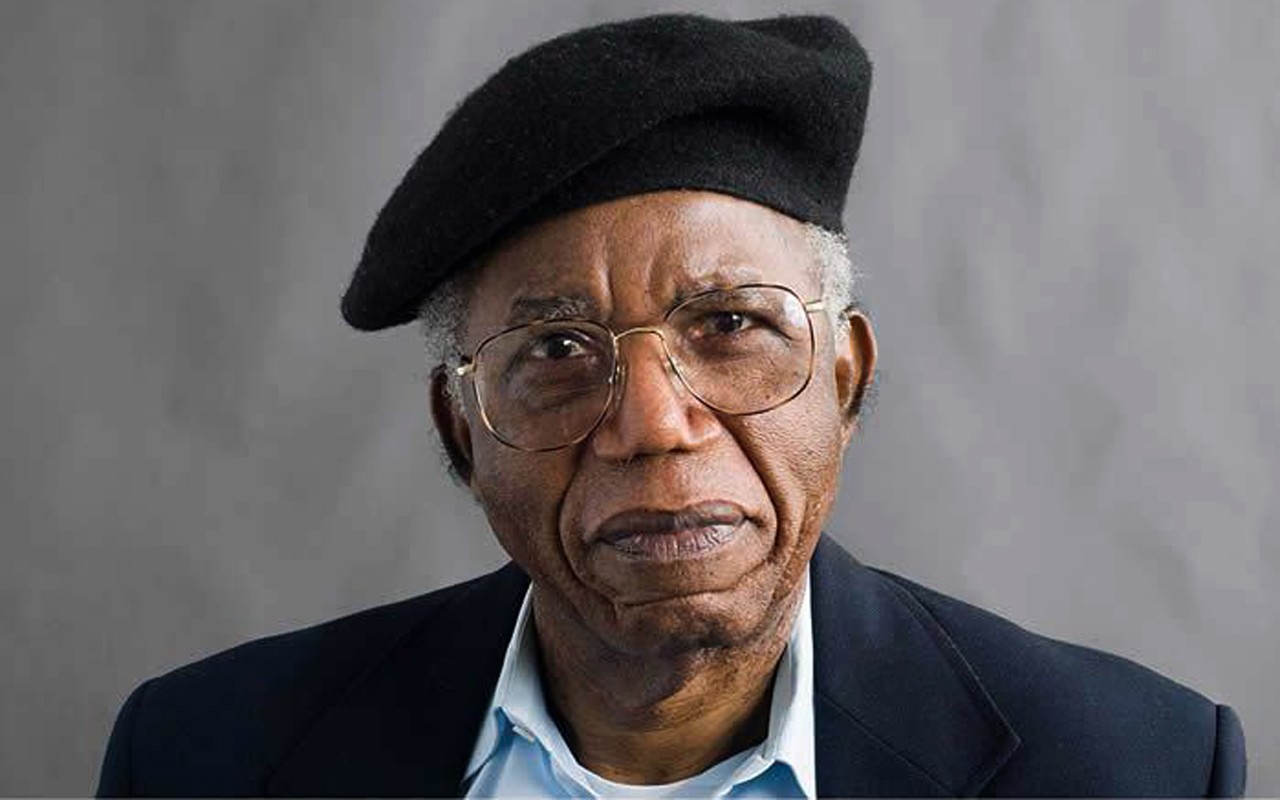

Chinua Achebe (1930–2013) is regarded as the father of modern African literature. He earned this accolade for his revered influence as an astute African author

for his seminal work, Things Fall Apart. His contribution to African literature is invaluable. First, he changed how the world views Africa by retelling Africa’s history and revealing its cultures and struggles in an authentic African voice. Again, Achebe used Things Fall Apart to broadcast Africa’s voice from centuries of being unheard. In Things Fall Apart, Achebe ensured that Africa was represented in global storytelling. He incorporated ancient traditions, language, and postcolonial critique into his work. Therefore, he redefined African literature as unique from Western literary traditions.

How Chinua Achebe Reclaimed the African Story

Before Achebe’s literary works, African characters in European works were often depicted as barbaric. For instance, in Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad uses derogatory terms to describe everything African. First, he claims that the continent is wild, dark, and impenetrable. Moreover, he refers to the African natives as “niggers”, “cannibals”, “criminals,” and “savages.” Achebe sees this as a great misrepresentation in his critique of Heart of Darkness. As such, he purposefully chooses to represent pre-colonial Africa as brimming with its unique civilization, hence Things Fall Apart.

Reclamation through Characterisation in Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart

In Things Fall Apart, Achebe tells the story of Okonkwo, a respected Igbo leader trying to protect traditions as European colonizers impose change. The novel portrays the rich culture of the Igbo people, including their religion, governance, family life, and oral storytelling traditions. Also, it offers a representative lens into other African cultures.

In this novel, Chinua Achebe never romanticizes Africa. Rather, he accurately and distinctively depicts the nuanced complexities of African societies and their people. Vividly, he reveals the challenges of gender roles and social rigidity through his characters. Yet, he refuses to let these define the African identity. By presenting complex multidimensional African characters, Achebe effectively challenges and counters colonial stereotypes and insists that African societies deserve the same literary depth as any other. Consequently, Achebe’s use of vivid characterization of Africans and the continent makes him successful in countering the pervasive pejorative European claims about Africa and its cultures.

Chinua Achebe’s Reclamation through Language as a Political Tool

Achebe wrote in English even though it was the colonizer’s language. Although critics like Ngugi Wa Thiong’o questioned his choice, Achebe’s answer was strategic. For him, English was his strategic way of reaching a global audience while reshaping the language to reflect African reality. Without a doubt, Achebe’s stylistic innovations complemented the weight of his themes, especially in exploring the legacy of colonialism.” Specifically, he infused English with Igbo proverbs, metaphors, and oral rhythms to create a unique style that was African. Despite this, it could be read worldwide. “Let no one be fooled by the fact that we may write in English,” Achebe once said, “for we intend to do unheard-of things with it.”

Consequently, Achebe’s approach turned English from a symbol of oppression into a tool of resistance. Achebe’s language has become a bridge between cultures. It has allowed African wisdom, humor, and worldview to reach readers worldwide. In doing so, he has given other African writers a new way to reappropriate colonial languages in their terms as political tools of subversion.

Chinua Achebe on Colonialism and Its Consequences

Achebe’s exploration of colonialism is even more potent through his masterful use of language, which he reclaims and reshapes to express African realities.” Knowing that colonialism affected Africans physically, psychologically, and culturally, Achebe’s works explored these by probing the negative impacts of colonialism on Africans. In Things Fall Apart, the coming of European missionaries caused unrest in Igbo society. Achebe captures how colonialism shattered traditional structures, sowed divisions, and left individuals like Okonkwo trapped between two worlds.

Furthermore, Achebe’s other books, Arrow of God and No Longer at Ease, demonstrate how colonialism damaged African traditions and led to endemic problems such as corruption and loss of identity even after independence. Yet, Achebe also showed African strength and Africans’ ability to adapt. His goal wasn’t just to blame the past but to help Africans heal and reclaim their identity.

A Global Literary Force

The Influence of Chinua Achebe

Achebe’s influence was worldwide. Things Fall Apart has been translated into more than 50 languages and has sold millions of copies. It is studied in classrooms across the world, not just as African literature but as a masterpiece of world literature.

He influenced generations of writers in Africa and beyond. He inspired authors like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Wole Soyinka, and Tsitsi Dangarembga to cite Achebe as his work permitted them to write authentically—to tell their own stories, in their original voices.

As a renowned author, Achebe was the founding editorof Heinemann’s African Writers Series, which became a major platform for African literature. Expectedly, he used his influence and resources to help other emerging African writers publish in the African Writers Series. Notably, Achebe’s influence helped authors like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o publish their early works. Achebe also helped to launch the careers of other literary voices, including Ghanaian poet and scholar Abena Busia. Truly, he was the first to publish Ama Busia’s works after a chance encounter in Manhattan. This way, Achebe ensured African literature grew and expanded, having a place on the world stage and continuously remaining relevant.

Chinua Achebe’s Literary Criticism and Global Dialogue

Chinua Achebe was not just a novelist; he was a critic and thinker. In his famous 1975 lecture “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness,” he argued that how Conrad portrayed Africans was dehumanizing and racist. Subsequently, this sparked debates about racism in classic Western books and re-examined the concepts of who gets to define civilization.

Rightly, Chinua Achebe insisted that African literature should be judged by African values, not through the lenses of European expectations. His essays and interviews consistently challenged intellectual laziness and pushed for a broader, more inclusive understanding of literature.

Substantially, his writings helped to start postcolonial studies, a field that explores how history, culture, and power shape stories and identities.

Today, Achebe’s influence is felt not only in literature departments but also in discussions of post-colonial narratives about politics, race, and education worldwide.

Chinua Achebe’s Humanist Vision

Indeed, Chinua Achebe’s work is deeply rooted in Nigeria, yet his themes are universal. Like humans, his characters wrestle with identity, pride, generational conflict, and fear of failure, which are never uniquely African. Achebe believed literature should reflect human experiences and help people understand each other better. So, he once said, “Art is man’s constant effort to create for himself a different order of reality from that which is given to him.” Through his stories, Achebe offered not just critique, but hope—hope that societies can evolve without losing their soul and that people can change without forgetting who they are.

Indeed, Chinua Achebe’s mission was more than writing books: he gave Africa its voice in literature. He diligently endeavored to correct false stories about African people, and he successfully showcased the deep beauty of African culture, inspiring writers around the world.

Fervently, his legacy lives on in the courage of every writer who tells his story honestly and proudly. Thanks to Achebe, African literature is evolving and reshaping global narratives, and is not just a response to the West. Now, it stands strong on its own, full of heart, history, and humanity.